The following classification covers a wide range of severity, and symptoms vary accordingly. Most non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy is asymptomatic, hence retinal examination is important to monitor for potentially vision-threatening progression. Maculopathy usually causes blurred vision in the affected eye.

Tight glucose control has been proven to slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Control of hypertension is also important.

Diabetic retinopathy

- Non-proliferative (retinal microhaemorrhage, cotton wool spots)

- Mild

- Moderate

- Severe

- Proliferative (abnormal new blood vessels grow on the optic disc or retina)

- Isolated

- With secondary vitreous haemorrhage

- With secondary tractional retinal detachment

Diabetic maculopathy

- Diabetic maculopathy

- Macular oedema

- Ischaemic maculopathy

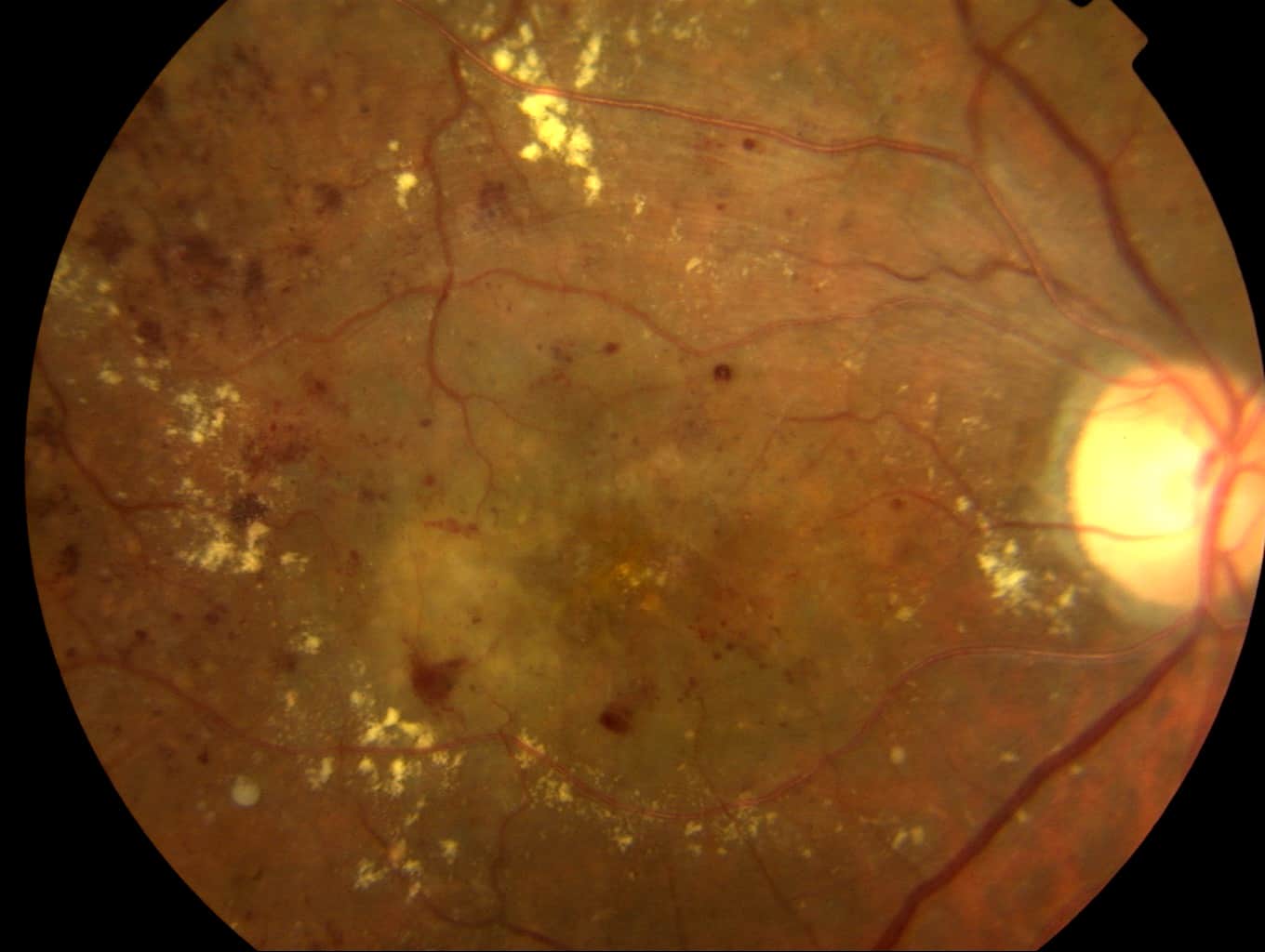

Severe diabetic retinopathy with extensive microhaemorrhages and exudates.

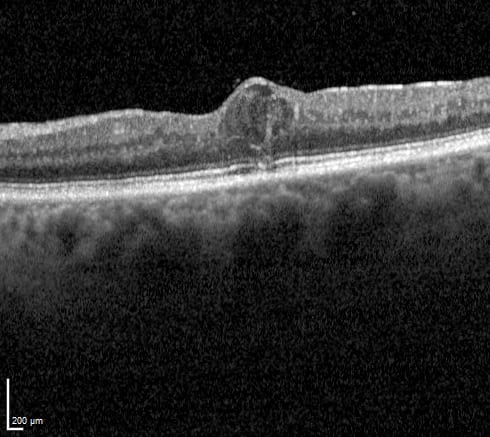

OCT showing thickening of the central macular (fovea) due to leaking fluid (diabetic macular oedema). The fluid is seen as a cystic space that elevates the inner retinal surface.

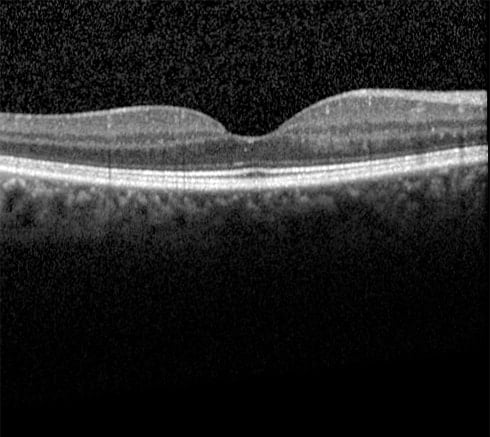

Normal OCT.

Monitoring and treatment of diabetic retinopathy

Those with no or mild diabetic retinopathy (background diabetic retinopathy or mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy) require regular screening. In the NHS this typically comprises annual fundus photographs via DECS (Diabetic Eye Complication Screening).

Moderate-to-severe non-proliferative retinopathy is often reviewed regularly by an ophthalmologist.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is usually treated with pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) laser. This aims to reduce the ischaemic drive that induces neovascularisation. PRP laser sacrifices some peripheral vision, but that is justified to reduce the risk of severe vision loss from vitreous haemorrhage.

Some studies suggest that repeated intravitreal injections of drugs targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are a good alternative to PRP, but this is not yet in common use and is a burdensome treatment due to repeat intravitreal injections.

Severe proliferative retinopathy not responding to PRP, non-clearing vitreous haemorrhage, or tractional retinal detachment from severe PDR may require vitrectomy with endoscopic PRP laser.

Treatment of diabetic maculopathy

Diabetic maculopathy manifests as ischaemia or macular oedema, and both may co-exist.

There is no proven treatment for ischaemic maculopathy.

Diabetic macular oedema may be observed if the fluid is far enough from the fovea, but if it involves or threatens the fovea then treatment is usually recommended.

Laser treatment was once the standard treatment, and it remains helpful for focal areas of leakage away from the fovea. Laser is usually applied to the area of macular thickening, avoiding the fovea itself (a foveal laser burn would damage vision). It may need to be repeated if macular oedema persists or recurs, but most patients usually only need one or two treatments.

The other main treatment is intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy. The most common drugs are aflibercept (Eylea), ranibizumab (Lucentis), and off-label bevacizumab (Avastin). These are highly effective but require repeated injections, typically about 4-8 over the first year.

Referral guidelines

Mild diabetic retinopathy can be referred routinely, moderate retinopathy within about 1-2 months, severe retinopathy within a month, and proliferative retinopathy within about 2 weeks.

Diabetic maculopathy does not require urgent referral, but would ideally be seen within about 4-6 weeks.

Further information on Diabetic Eye Disease is available in the patient information leaflet.